Interesting article from The New York Times Magazine. Here are a few extracts:

The aim of fantasy, after all, is to awaken something sleeping in our imaginations — and Martin and the show’s creators, David Benioff and D. B. Weiss, embrace this task with a passion, skirting dull expository groundwork in the early episodes in favor of those elements that are just preposterous enough to mirror the depravity of contemporary life. We dive right into orgiastic feasts, murderous snow zombies, Faustian bargains made with primitives and feverish acts of incest. This is fantasy, after all — and medieval fantasy at that — so why not? Naked breasts are intended to tumble from their leather bustiers, dwarves and bastards are meant to address each other as “Dwarf” and “Bastard,” and coitus should never, ever be missionary style.

In this way, fantasy as a genre seems to have an almost unfair advantage at allegorically chronicling our age. Elsewhere, the crudeness and savagery of modern life are artfully encoded in the palm-sweating desperation of the meth-dealing dad in “Breaking Bad,” the terse detachment of the pill-popping mom in “Nurse Jackie” or the quiet machinations of the enigmatic assassin in “Dexter.” But that brand of darkness has so thoroughly become the default syntax of cable dramas that even these sensational figures can’t quite jar us out of our somnambulant state. We apparently require gigantic walls of ice, supernatural wolf puppies, gory jousts, dragon eggs and a nomadic warrior who looks like Dave Navarro after heavy steroid use. Maybe it takes the grand scale of sybaritic kings and imaginary kingdoms to do justice to the perversions and the nihilism of post-empire America.

[...]

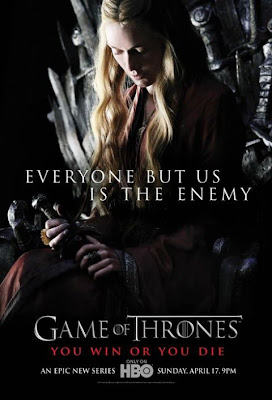

Fantasy, for all its imaginative potential, is fertile ground for nihilists. This can be useful. For one, it enables its writers to personalize viciousness in ways that could never be accomplished in contemporary realism. When, on “Game of Thrones,” a princess begs her brother not to force her to marry a savage whose language she doesn’t understand (a situation not unfamiliar to your average single female), he coldly informs her that he would let the entire savage tribe have its way with her if that might restore him to power. (“All 40,000 men and their horses, too, if that’s what it took.”) When the queen’s son tries to convince her that a rival clan is their enemy, she spits, “Everyone who isn’t us is an enemy.” By repositioning a familiar message — “If you’re not with us, you’re against us” — in medieval-fantasy terms, the show’s creators force us to view its ghastliness with fresh eyes. In contrast to the uneasy alienation of dropping bombs on countries thousands of miles away, “Game of Thrones” presents its carnage in such extreme close-up that it can’t be ignored. Heads are sliced off with stunning regularity, innocents are harmed or killed without much hesitation and the camera lingers lovingly on each surge of blood.

[...]

All of which is very somber — and a little odd, when you think about it. Even with countless horrors on the way, wouldn’t there be at least one unshakable optimist in the bunch? Isn’t that how we, in the real world, get through life? Irrational optimism in the face of looming bleakness? Yet in this brand of fantasy, grim-faced nihilism isn’t just a default philosophy; it’s a foundational religion.

And why, while we’re on the subject, do the authors of medieval fantasy so often restrict themselves to sullen thugs and solemn royals, instead of serving up a more varied palette of characters to reflect the stubbornly cheerful drones and twitchy neurotics of modern times? Why do authors limit themselves to somber dialogue that they consider period-appropriate, a compulsion as specious as associating France with French fries jokes? Whereas sci-fi fantasies gamely employ playful, contemporary dialogue, Dark-Ages-flavored narratives appear to require the repetitive, sludgy talk of honor and impending bloodshed. Aside from Tyrion Lannister (Peter Dinklage), a snarky dwarf, and Littlefinger (Aidan Gillen), a crafty adviser to the king, the characters of “Game of Thrones” rarely speak without sounding ponderous and sour. Unless two characters are discussing the joys of sex or drinking, there’s not much lightness; only anger, disillusionment and apprehension.

Follow this link for the full piece.